The British West Indies Regiment

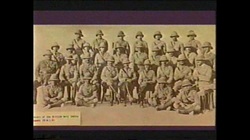

The British West Indies Regiment was a unit of the British Army during the First World War, formed from volunteers from British colonies in the West Indies.

The 1st Battalion was formed in September 1915 at Seaford, Sussex, England. It was made up of men from:

The 1st Battalion was formed in September 1915 at Seaford, Sussex, England. It was made up of men from:

- British Guiana—A Company.

- Trinidad—B Company.

- Trinidad and St Vincent—C Company.

- Grenada and Barbados—D Company.

Eugent Clarke

Jamaican who fought in Somme will meet the Queen

By Andrew Alderson and David Paulin

12:01AM GMT 17 Feb 2002

EUGENT CLARKE, a 108-year-old war veteran who fought at the Battle of the Somme more than 85 years ago, is to meet the Queen and Prince Philip in Jamaica tomorrow on the first leg of the monarch's Golden Jubilee Commonwealth tour.

Mr Clarke, a native Jamaican, had to endure fierce shelling on the Western Front and racism from his fellow soldiers after volunteering to risk his life for the British Empire in the First World War.

In an interview with The Telegraph at his home near the Jamaican capital of Kingston, Mr Clarke spoke of his excitement at meeting the Queen during the first official engagement of her tour when he will be joined by other war veterans.

Speaking haltingly and in a barely audible whisper, he said: "I feel very proud to see her because she is from England, and England is my mother country." His voice may have been shaky but his dark eyes twinkled behind thick glasses.

Mr Clarke recalled the Somme, when shells rained down, bodies of soldiers piled up and "the mud would drown you" in the trenches. He also remembered a brief respite from the conflict when George V visited the troops in France.

He said that he had been looking for adventure when he enlisted, but he was also motivated by his allegiance to the Crown. His wartime activities took him to Italy, Egypt, Canada and Britain.

Mr Clarke set sail for Europe as part of the British West Indies Regiment in March 1916. Roughly 10,000 Jamaicans served in the First World War. About 1,000 of them died.

His volunteer unit of the British West Indies Regiment was known as "coloured" at a time when the Services were segregated and black troops were assigned to "labour battalions".

"They were in the front lines and were exposed to shelling and active fire. But they also did things like digging trenches and laying telephone cables," said Major-General Robert Neish, now retired, who headed the Jamaica Defence Force and is now chairman of the Jamaican Legion of veterans affiliated to the British Commonwealth Ex-Services League.

Mr Clarke proudly wore his old blue uniform and three medals for his interview with The Telegraph: it is how he plans to appear before the Queen. He received France's Legion of Honour, a campaign medal and a war medal for his service.

The veteran played down the racial discrimination that black soldiers faced from fellow soldiers, including an incident famous in the Caribbean when his regiment staged a violent protest against discrimination in the closing days of the war in the winter of 1918.

He says he was not involved, though other troops he knew were disciplined. When asked of his wartime role, Mr Clarke simply said: "I have no regrets." Returning from the war, Mr Clarke found his mother had died and his father had remarried, while his teenage sweetheart had married another man.

There were few opportunities in Jamaica so he headed to Cuba, where he worked in the sugar cane fields for 10 years.

After returning to Jamaica he worked on farms planting sugar cane, yams and potatoes. During the Second World War he served as a security guard at an American airbase. Mr Clarke did get married, but his wife, Margaret, died 37 years ago. He has no children.

Mr Clarke, who enjoys history books, English literature and poetry, receives £15 a month from the British Commonwealth Ex-Services League which is being supported during the Golden Jubilee year by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh.

Today he lives 30 miles southwest of Kingston. It is close to where he grew up and he is respected by local people who affectionately call him "Pa".

Velet Miller-Lewis, a semi-retired nurse who helps care for Mr Clarke, described him as an optimist who is deeply religious. "He holds on to God. He does not worry about anything," she said.

Jamaican who fought in Somme will meet the Queen

By Andrew Alderson and David Paulin

12:01AM GMT 17 Feb 2002

EUGENT CLARKE, a 108-year-old war veteran who fought at the Battle of the Somme more than 85 years ago, is to meet the Queen and Prince Philip in Jamaica tomorrow on the first leg of the monarch's Golden Jubilee Commonwealth tour.

Mr Clarke, a native Jamaican, had to endure fierce shelling on the Western Front and racism from his fellow soldiers after volunteering to risk his life for the British Empire in the First World War.

In an interview with The Telegraph at his home near the Jamaican capital of Kingston, Mr Clarke spoke of his excitement at meeting the Queen during the first official engagement of her tour when he will be joined by other war veterans.

Speaking haltingly and in a barely audible whisper, he said: "I feel very proud to see her because she is from England, and England is my mother country." His voice may have been shaky but his dark eyes twinkled behind thick glasses.

Mr Clarke recalled the Somme, when shells rained down, bodies of soldiers piled up and "the mud would drown you" in the trenches. He also remembered a brief respite from the conflict when George V visited the troops in France.

He said that he had been looking for adventure when he enlisted, but he was also motivated by his allegiance to the Crown. His wartime activities took him to Italy, Egypt, Canada and Britain.

Mr Clarke set sail for Europe as part of the British West Indies Regiment in March 1916. Roughly 10,000 Jamaicans served in the First World War. About 1,000 of them died.

His volunteer unit of the British West Indies Regiment was known as "coloured" at a time when the Services were segregated and black troops were assigned to "labour battalions".

"They were in the front lines and were exposed to shelling and active fire. But they also did things like digging trenches and laying telephone cables," said Major-General Robert Neish, now retired, who headed the Jamaica Defence Force and is now chairman of the Jamaican Legion of veterans affiliated to the British Commonwealth Ex-Services League.

Mr Clarke proudly wore his old blue uniform and three medals for his interview with The Telegraph: it is how he plans to appear before the Queen. He received France's Legion of Honour, a campaign medal and a war medal for his service.

The veteran played down the racial discrimination that black soldiers faced from fellow soldiers, including an incident famous in the Caribbean when his regiment staged a violent protest against discrimination in the closing days of the war in the winter of 1918.

He says he was not involved, though other troops he knew were disciplined. When asked of his wartime role, Mr Clarke simply said: "I have no regrets." Returning from the war, Mr Clarke found his mother had died and his father had remarried, while his teenage sweetheart had married another man.

There were few opportunities in Jamaica so he headed to Cuba, where he worked in the sugar cane fields for 10 years.

After returning to Jamaica he worked on farms planting sugar cane, yams and potatoes. During the Second World War he served as a security guard at an American airbase. Mr Clarke did get married, but his wife, Margaret, died 37 years ago. He has no children.

Mr Clarke, who enjoys history books, English literature and poetry, receives £15 a month from the British Commonwealth Ex-Services League which is being supported during the Golden Jubilee year by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh.

Today he lives 30 miles southwest of Kingston. It is close to where he grew up and he is respected by local people who affectionately call him "Pa".

Velet Miller-Lewis, a semi-retired nurse who helps care for Mr Clarke, described him as an optimist who is deeply religious. "He holds on to God. He does not worry about anything," she said.

Gershom Browne (8 August 1898 – 6 December 2000) was the last known Guyana First World War veteran, he served in 'C' company 1st British West Indies Regiment and fought on the Western Front during the war. He fought against the Turkish Army who were allies of the German Army. He died on 6 December 2000; at death he was the last Guyana vetera of the First World War

Clifford Powell, Jamaica, Served with the British West Indies Regiment. Emigrated to Cuba at the end of World War 1.

Born in St Michael, Barbados, Wickham served in Palestine in the British West Indies Regiment of World War I[1 and after his return to Barbados joined The Herald newspaper, edited by Clement A. Inniss, in 1919 and wrote for universal adult suffrage in a column under the title "Audax" (the listener). Wickham became sole editor of the newspaper following Inniss's early death.

In 1921, Wickham summarized attitudes of members of theBarbadian House of Assembly in the first years of the twentieth century as follows: "There is no sense of duty to the individual of the island as a whole. There is no sense of responsibility for broad and reasonable treatment. There is merely a sense of class." By the late 1920s, he developed a reputation for being one of the foremost critics of the plantocracy and brought into the open that, although patterned after British common law, Barbadian law in 1900 was in a sense an objective code of rules whose ethical validity transcended the interests and attitudes of several classes on the island.

In 1921, Wickham summarized attitudes of members of theBarbadian House of Assembly in the first years of the twentieth century as follows: "There is no sense of duty to the individual of the island as a whole. There is no sense of responsibility for broad and reasonable treatment. There is merely a sense of class." By the late 1920s, he developed a reputation for being one of the foremost critics of the plantocracy and brought into the open that, although patterned after British common law, Barbadian law in 1900 was in a sense an objective code of rules whose ethical validity transcended the interests and attitudes of several classes on the island.

Soldier of British West Indies Regiment in Egypt 1917.

THE STORY OF THE BRITISH WEST INDIES REGIMENT IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

In 1915 Britain's War Office, which had initially opposed recruitment of West Indian troops, agreed to accept volunteers from the West Indies.

A new regiment was formed, the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR), which served in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Some of the items below are on display in our First World War Galleries. You can use this article to guide you to their location in the galleries. We have also included additional information that sheds light on the story of the West Indies' contribution to the war effort.

ON THE WESTERN FRONT

The formation of the BWIR did not give soldiers from the West Indies the opportunity to fight as equals alongside white soldiers. Instead, the War Office largely limited their participation to 'labour' duties. The use of BWIR soldiers in supporting roles intensified during the Battle of the Somme as casualties among fighting troops meant that reinforcements were needed in the front line.

BWIR troops were engaged in numerous support roles on the Western Front, including digging trenches, building roads and gun emplacements, acting as stretcher bearers, loading ships and trains, and working in ammunition dumps. This work was often carried out within range of German artillery and snipers. In July 1917, 13 men from the BWIR were killed by shell fire and aerial bombardment.

In 1917 Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig said of the BWIR, '[Their] work has been very arduous and has been carried out almost continuously under shell-fire. In spite of casualties the men have always shown themselves willing and cheerful workers, and the assistance they have rendered has been much appreciated by the units to which they have been attached and for whom they have been working. The physique of the men is exceptional, their discipline excellent and their morale high'.

Several battalions of the BWIR were deployed to Egypt and Palestine. Here too, they were mostly used in support functions, such as guarding prisoners and holding reserve posts and outposts, although in 1916 the War Office relaxed its opposition to the BWIR being used in combat.

Men of the BWIR creating dugouts in Palestine.

First World War sign pointing to Jerusalem.

This sign points to a famous British victory, the capture of Jerusalem in 1917. Yet this was not the end of the struggle for Palestine. Soldiers of the BWIR arrived in September 1918 and played their part in the fighting which would secure victory the following month. In one action, the 2nd Battalion BWIR was given orders to clear enemy posts close to the British line in Palestine. This involved advancing across over 5km of open land under heavy fire. The objective was achieved with nine men killed and 43 wounded. Two men, Lance Corporal Sampson and Private Spence, were awarded the Military Medal for bravery during the action. On 20 September, after the campaign, the commanding officer of the BWIR, Major General Sir Edward Chaytor, wrote, 'Outside my own division there are no troops I would sooner have with me than the BWIs who have won the highest opinions of all who have been with them during our operations here'.

The 2nd Battalion, West India Regiment embarking for active service in East Africa. Photo courtesy Australian War Memorial.

WEST INDIAN SOLDIERS IN AFRICA

In addition to the BWIR, the West Indies contributed men through the West India Regiment (WIR), which consisted mainly of black African soldiers. The WIR had existed since 1795 and served Britain until 1927, when it was disbanded for economic reasons. During the First World War, the regiment was deployed in East Africa as well as Togoland and Cameroon. Togoland (which now forms modern day Togo and part of Ghana) and Cameroon were German colonies with important wireless stations. The first two years of the war saw a multi-national force - including West Indians, Nigerians, Ghanians (Gold Coast) and Indians - capture Togoland and Cameroon from Germany.

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

In July 1916, 500 men of the BWIR were also sent to fight in German East Africa. There they were engaged in guarding the railway line captured from German forces, manning communications posts, and finding and capturing German ammunition dumps. This was a difficult and little-remembered posting. The rainy season brought challenging conditions, and soldiers suffered from malaria, exposure and lack of supplies including clothing and food. Letters were rarely delivered due to the remote location.

HARSH CONDITIONS AND DISCRIMINATION

Cigarette cases such as this one were presented to all ranks of the British West Indies Regiment for Christmas in 1917. While gifts such as these were always welcome, they were scant consolation for what many BWIR men experienced. Poor accommodation in training camps in England resulted in men of the BWIR developing frostbite and pneumonia.

Cigarette case presented to all ranks of the British West Indies Regiment, Christmas 1917.

In March 1916, a ship transporting BWIR men from Jamaica, the SS Verdala, was diverted into a blizzard near Halifax, Canada, to avoid any lurking German warships. As a result of inadequate equipment, over 600 men suffered from exposure and frostbite, 106 men required amputations and at least five men died.

West Indian troops also often had to deal with racial discrimination from their fellow soldiers and the military authorities. In 1918 BWIR soldiers were denied a pay rise given to other British troops on the basis that they had been classified as 'natives'. The increase was eventually granted following protests by serving soldiers and the various island governments.

Tensions brought about by this sort of treatment eventually came to a head in Taranto, Italy in December 1918. Frustrated by their continued use as labourers whilst waiting for demobilisation, men of the 9th Battalion attacked their officers in a mutiny that lasted four days before being quelled.

A number of BWIR soldiers were awarded gallantry medals during the war, including five Distinguished Service Orders, nineteen Military Crosses, eleven Military Crosses with Bar, eighteen Distinguished Conduct Medals, as well as 49 Mentions in Despatches. Among other soldiers from the West Indies who were awarded decorations was future Premier of Jamaica, Norman Manley, who received the Military Medal.

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919, by William Orpen

By the end of the First World War, 185 men from the BWIR had been killed in action and 1,071 had died of sickness. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission tends the graves of BWIR men in cemeteries in Britain, the West Indies, Belgium, Egypt, France, Italy, Iraq, Israel and Palestine, and Tanzania. Many of the West Indian men who returned from fighting in the 'Great War' came home with a sense of grievance. They had answered Britain’s call. They had fought in a war that was not of their own making yet played their part in the eventual defeat of Germany and its allies. But they had still faced discrimination for their colour.

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles was meant to create not just a peaceful world but a fairer one as well. Yet this vision would not include self-determination for many of the subject peoples of Britain’s non-white colonies. In supporting the war effort many West Indians had hoped for change, but it would take several decades, and another world war, for the islands to gain independence from Britain.

In 1915 Britain's War Office, which had initially opposed recruitment of West Indian troops, agreed to accept volunteers from the West Indies.

A new regiment was formed, the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR), which served in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Some of the items below are on display in our First World War Galleries. You can use this article to guide you to their location in the galleries. We have also included additional information that sheds light on the story of the West Indies' contribution to the war effort.

ON THE WESTERN FRONT

The formation of the BWIR did not give soldiers from the West Indies the opportunity to fight as equals alongside white soldiers. Instead, the War Office largely limited their participation to 'labour' duties. The use of BWIR soldiers in supporting roles intensified during the Battle of the Somme as casualties among fighting troops meant that reinforcements were needed in the front line.

BWIR troops were engaged in numerous support roles on the Western Front, including digging trenches, building roads and gun emplacements, acting as stretcher bearers, loading ships and trains, and working in ammunition dumps. This work was often carried out within range of German artillery and snipers. In July 1917, 13 men from the BWIR were killed by shell fire and aerial bombardment.

In 1917 Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig said of the BWIR, '[Their] work has been very arduous and has been carried out almost continuously under shell-fire. In spite of casualties the men have always shown themselves willing and cheerful workers, and the assistance they have rendered has been much appreciated by the units to which they have been attached and for whom they have been working. The physique of the men is exceptional, their discipline excellent and their morale high'.

Several battalions of the BWIR were deployed to Egypt and Palestine. Here too, they were mostly used in support functions, such as guarding prisoners and holding reserve posts and outposts, although in 1916 the War Office relaxed its opposition to the BWIR being used in combat.

Men of the BWIR creating dugouts in Palestine.

First World War sign pointing to Jerusalem.

This sign points to a famous British victory, the capture of Jerusalem in 1917. Yet this was not the end of the struggle for Palestine. Soldiers of the BWIR arrived in September 1918 and played their part in the fighting which would secure victory the following month. In one action, the 2nd Battalion BWIR was given orders to clear enemy posts close to the British line in Palestine. This involved advancing across over 5km of open land under heavy fire. The objective was achieved with nine men killed and 43 wounded. Two men, Lance Corporal Sampson and Private Spence, were awarded the Military Medal for bravery during the action. On 20 September, after the campaign, the commanding officer of the BWIR, Major General Sir Edward Chaytor, wrote, 'Outside my own division there are no troops I would sooner have with me than the BWIs who have won the highest opinions of all who have been with them during our operations here'.

The 2nd Battalion, West India Regiment embarking for active service in East Africa. Photo courtesy Australian War Memorial.

WEST INDIAN SOLDIERS IN AFRICA

In addition to the BWIR, the West Indies contributed men through the West India Regiment (WIR), which consisted mainly of black African soldiers. The WIR had existed since 1795 and served Britain until 1927, when it was disbanded for economic reasons. During the First World War, the regiment was deployed in East Africa as well as Togoland and Cameroon. Togoland (which now forms modern day Togo and part of Ghana) and Cameroon were German colonies with important wireless stations. The first two years of the war saw a multi-national force - including West Indians, Nigerians, Ghanians (Gold Coast) and Indians - capture Togoland and Cameroon from Germany.

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

In July 1916, 500 men of the BWIR were also sent to fight in German East Africa. There they were engaged in guarding the railway line captured from German forces, manning communications posts, and finding and capturing German ammunition dumps. This was a difficult and little-remembered posting. The rainy season brought challenging conditions, and soldiers suffered from malaria, exposure and lack of supplies including clothing and food. Letters were rarely delivered due to the remote location.

HARSH CONDITIONS AND DISCRIMINATION

Cigarette cases such as this one were presented to all ranks of the British West Indies Regiment for Christmas in 1917. While gifts such as these were always welcome, they were scant consolation for what many BWIR men experienced. Poor accommodation in training camps in England resulted in men of the BWIR developing frostbite and pneumonia.

Cigarette case presented to all ranks of the British West Indies Regiment, Christmas 1917.

In March 1916, a ship transporting BWIR men from Jamaica, the SS Verdala, was diverted into a blizzard near Halifax, Canada, to avoid any lurking German warships. As a result of inadequate equipment, over 600 men suffered from exposure and frostbite, 106 men required amputations and at least five men died.

West Indian troops also often had to deal with racial discrimination from their fellow soldiers and the military authorities. In 1918 BWIR soldiers were denied a pay rise given to other British troops on the basis that they had been classified as 'natives'. The increase was eventually granted following protests by serving soldiers and the various island governments.

Tensions brought about by this sort of treatment eventually came to a head in Taranto, Italy in December 1918. Frustrated by their continued use as labourers whilst waiting for demobilisation, men of the 9th Battalion attacked their officers in a mutiny that lasted four days before being quelled.

A number of BWIR soldiers were awarded gallantry medals during the war, including five Distinguished Service Orders, nineteen Military Crosses, eleven Military Crosses with Bar, eighteen Distinguished Conduct Medals, as well as 49 Mentions in Despatches. Among other soldiers from the West Indies who were awarded decorations was future Premier of Jamaica, Norman Manley, who received the Military Medal.

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919, by William Orpen

By the end of the First World War, 185 men from the BWIR had been killed in action and 1,071 had died of sickness. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission tends the graves of BWIR men in cemeteries in Britain, the West Indies, Belgium, Egypt, France, Italy, Iraq, Israel and Palestine, and Tanzania. Many of the West Indian men who returned from fighting in the 'Great War' came home with a sense of grievance. They had answered Britain’s call. They had fought in a war that was not of their own making yet played their part in the eventual defeat of Germany and its allies. But they had still faced discrimination for their colour.

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles was meant to create not just a peaceful world but a fairer one as well. Yet this vision would not include self-determination for many of the subject peoples of Britain’s non-white colonies. In supporting the war effort many West Indians had hoped for change, but it would take several decades, and another world war, for the islands to gain independence from Britain.

|

British West Indies Regiment

Formed in 1915, this British Army regiment was composed of volunteers from the West Indies and served in various theatres of the First World War. It was disbanded in 1921, shortly after the end of the conflict. Origins On the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18), thousands of men from the West Indies volunteered to support the British imperial war effort. Many joined the West India Regiment, while others made their own way to Britain, enlisting in other units of the British Army. Despite the growing numbers, the War Office was reluctant to deploy these volunteers as a new combat unit. Instead, they regarded them as potential labourers, who could assist in essential, but menial, logistic roles. However, following the intervention of King George V, the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) was formed in 1915. The new regiment raised 11 battalions during the war and over 15,600 men enlisted. Most of Britain's Caribbean colonies were represented among its ranks, but the majority of soldiers were from Jamaica. Wartime service In accordance with the colonial policies of the time, the War Office did not want to have non-white troops fighting against white troops. As a result, the regiment's 1st and 2nd Battalions were sent to Egypt - along with the 5th, a training battalion to fight the Ottoman Turks. They served with distinction, taking part in actions in Palestine and the Jordan Valley. The other BWIR battalions were sent to Europe, where they were employed as labourers or pioneers, providing vital logistic support on the Western Front. They also helped to guard prisoners of war. They served during some of the most hard-fought battles, including the Somme (1916), Arras (1917) and Passchendaele (1917). Altogether, nearly 1,500 men of the BWIR were killed during the conflict. Demobilisation At the end of the war, the regiment's various battalions were sent to Taranto in Italy to await passage home. Here, they were subjected to degrading and racist treatment from certain officers, including being tasked with digging latrines for the Italian Labour Corps. They were also initially denied a pay rise that had been awarded to other troops. On 6 December 1918, a mutiny broke out and the men of the BWIR were eventually escorted back to Britain under armed guard. Such unrest was not uncommon around this time, as tired and frustrated soldiers spent months awaiting ships to take them home. Legacy Despite being barred from attending the 1919 Victory Parade in London, the men were welcomed home to the Caribbean as heroes. Many veterans of the BWIR went on to become leaders in the West Indies. The regiment was disbanded in 1921. None of its battle honours were inherited by future West Indies regiments. The West India Regiments Raised in the 1790s to defend Britain's Caribbean colonies, the West India Regiments fought as infantry in several campaigns. They remained a part of the British Army until disbandment in 1927. |

|